Honest Lawbreakers

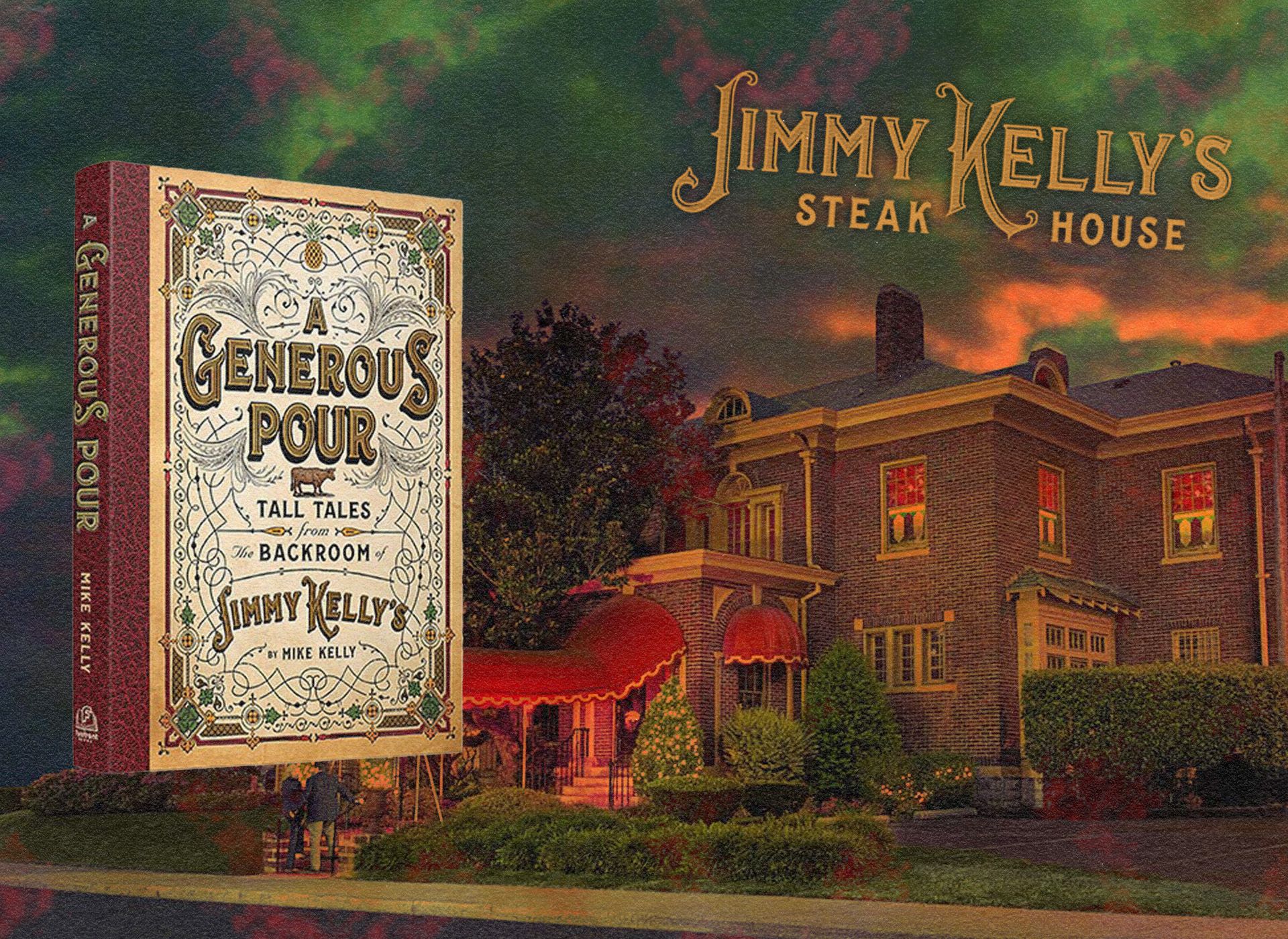

A Review of A Generous Pour: Tall Tales from the Backroom of Jimmy Kelly’s By Mike Kelly

In Orthodoxy (1908), G. K. Chesterton writes, “Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.” Chesterton never visited Jimmy Kelly Steakhouse; it opened in 1934, two years before his death. However, he would almost certainly have appreciated it—not only for the famous cuts of meat and full bar, perfect for a notorious gourmand with a permissive attitude toward drinking but also for the sacred protection of its legacy.

The Kelly family has been integral to Nashville’s evolution since before the Civil War. James Kelly first immigrated to the city in his teens with little more than the copper piping that would allow him to carve out a living with a whiskey still. That roughshod spirit prevailed through the generations. His son, John Kelly, stood defiant against Prohibition by selling alcohol under the guise of his ice business, and his grandson, Jimmy, opened the now-famous local spot and made it a hub for overturning the state and city’s dry laws.

Now, current restaurant proprietor and fourth-generation Nashvillian Mike Kelly has collected his family’s history in A Generous Pour: Tall Tales from the Backroom of Jimmy Kelly’s with assists from some of his most loyal customers; it is the rare book that caters to nearly as many different demographics as the establishment that serves as its subject. Ostensibly a local interest book for Kelly’s regulars, A Generous Pour is also a concise history of the moonshine trade, a tribute to local eating, and a pointed assessment of the South’s evolution from Reconstruction to its modern-day status as an economic behemoth that makes it a worthwhile read as breezy as it is substantive.

The site of an endless stream of graduation dinners and backroom deals, Jimmy Kelly’s has long had to negotiate similar identity tensions as the city it calls home. It's a steakhouse that still offers the same bacon and blue cheese Faucon Salad and prime cuts of beef in defiance of the celebrity chef, James Beard-chasing tenor of our current restaurant scene. It’s a place where tourists intermingle with policy wonks and lawmakers on a sojourn from the Capitol that revels in its populism despite boasting both a general and regulars’ entrance. It’s also a dining destination that never wavers in upholding Nashville traditions–though its current location at 217 Louise Avenue, an elegantly decorated Victorian respite from the industrial minimalism of Vanderbilt’s sprawl, is technically its third home.

In theory, such a microhistory of a local restaurant shouldn’t be of much interest to anyone beyond its dedicated customers and those perusing copies in the foyer while waiting for a table. However, Kelly is as gifted a writer as he is a restaurateur, effortlessly threading the development of Jimmy Kelly’s within the broader story of the city and region over the past century. Likewise, Kelly is not content with the recitation of a dry laundry list of trivia that only appeals to those in the know; instead, his scrapbook of Jimmy Kelly’s makes some refreshing and cogent arguments about Southern politics and history not out of place in an academic study.

A Generous Pour’s central thesis explores how state and federal government intervention has long served as the primary threat to the country’s entrepreneurial spirit and general welfare. As the temperance movement encroached on his saloon, Mike’s grandfather, John, met with his bishop about the prospect of entering the bootlegging trade. A devout Catholic, he wanted to respect the law, but also witnessed how other bar owners who saw it as their duty to directly provide for Nashville’s underclass faced financial ruin that put an end to their charity as teetotalers' well-intended interventions further eroded the city’s social fabric. Kelly’s solution was to define a code of honest lawbreaking that allowed him to provide for his family while protecting those Nashvillians who flouted state and federal temperance laws from the dangers of bathroom gin and other forms of toxic, unbonded alcohol.

Such infringements on personal freedoms also factor into Jimmy Kelly’s legacy as both a target of government raids for serving liquor by the drink and as the headquarters of the Watauga Association of Nashvillians, who realized how the regressive post-Prohibition dry laws hindered the city’s economic growth and decided to oppose the national religious leaders who also called the city home. Kelly’s hilarious recounting of how legendary publicist Hal Kennedy ended thirty minutes of paid primetime the night before the liquor referendum with three minutes of boll weevils munching on leaves to compel viewers to switch channels before the pro-dry camp aired their case is a standout moment among standout moments.

While such conflicts between individual freedom and the state remain in focus throughout the book, Kelly also provides a depiction of the press that exposes the much-lauded notion of journalistic objectivity as pure myth. From the politician turned pro-temperance editor of the Nashville Tennessean, Edward Ward Carmac, dying in a shootout with Democratic lawmaker and Nashville American editor, John Duncan Cooper, to more recent Kelly’s regular Tom Ingram spearheading Lamar Alexander’s famous red-and-black plaid shirt aesthetic during a now-legendary gubernatorial campaign, Kelly implies that politics and journalism remain inexorably linked among the powers that be.

Yet, in this time of political division, Kelly also displays an optimism that spaces like his steakhouse can serve as catalysts for negotiation and camaraderie. The last third of A Generous Pour consists of musings from some of the city’s most influential citizens, including Democratic party icons Jimmy Naifeh and former mayor Karl Dean, as well as Bill Lee’s Deputy Governor and Commissioner of Transportation, Butch Eley. Their anecdotes lend credence to the idea that locals putting aside party politics for the better of one’s hometown is the bedrock of initiatives like the Music City Center or Nissan Stadium, which have led to Nashville’s “It City” status (the city’s immense debt notwithstanding). Despite such a rosy outlook, the book tellingly makes no mention of Megan Barry, the Cooper brothers, or other, more recent polarizing local politicians.

Such contributions from lifelong Kelly’s patrons fill the gaps in A Generous Pour’s multigenerational history of the city, but they also lead to the book ending on a rather scattershot note. Kelly’s sketches of Nashville, from his grandfather’s ice delivery business and 216 Dinner Club to Jimmy Kelly’s initial Belle Meade location to its current iteration (with surprise appearances by Al Capone and Jimmy Hoffa), form a captivating tour through time. While the main section of the book ends on the high note of Mike’s father begrudgingly allowing Bob Dylan to become the first person to wear jeans in his establishment, readers may wonder how the project would have played out if the same authorial voice carried the story of Kelly’s into the present day. Regardless, A Gifted Pour remains a deft case for the distinctness of Southern culture and an unexpected defense of the entrepreneurial spirit in the face of crippling government interference that fully illustrates the importance of tradition as a democracy of the dead.

Order A Generous Pour from Amazon here.