Asteroid City’s American Trauma

The latest from Wes Anderson probes our personal and national loss as only he could.

The fourth in a series on exploiting tragedy in the movies. Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

Shortly before the grand finale of Wes Anderson’s breakout film Rushmore, dilatant teen Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman) accosts millionaire Herman Blume (Bill Murray). Both are vying for the affections of Miss Cross (Olivia Willams) an elementary school teacher at the prestigious academy Max has just flunked out of. As an annoyed Blume drives off, Max bellows, “I saved Latin. What did you ever do?”

In the intervening years between Rushmore’s release and Anderson’s latest, Asteroid City, the Austin, TX, indie filmmaker has become the only director who could rival Quentin Tarantino as the poster child for the contemporary American cinema. Anderson’s bright palette and obsessively symmetrical compositions have become an aesthetic unmoored from his movies, leading to an onslaught of parodies that have often garnered audiences that exceed that of his work. The Instagram page “Accidentally Wes Anderson” has spawned a travel and apparel brand that, armed with the director’s tentative blessing, has built a fan base requiring only a cursory knowledge of his filmography.

However, what makes Anderson’s films resonate is not his easily appropriated aesthetic but his keen understanding of his characters’ delusions. In Max’s mind, a petition to save classics instruction at a school where he can’t hack it puts him on equal footing with a successful but sad industrialist. It’s a ludicrous level of self-absorption, but Anderson doesn’t hold Max up for ridicule; he wants the audience to feel his pain and reflect on its own youthful arrogance. A filmmaker that can convey such depths with a seemingly throwaway line doesn’t need the endlessly memeable style that made Anderson famous. But his fans and critics have proven they don’t want to acknowledge the despair in their own lives for which Anderson’s work has long reminded them they are culpable beneath its vibrant and cheerful veneer.

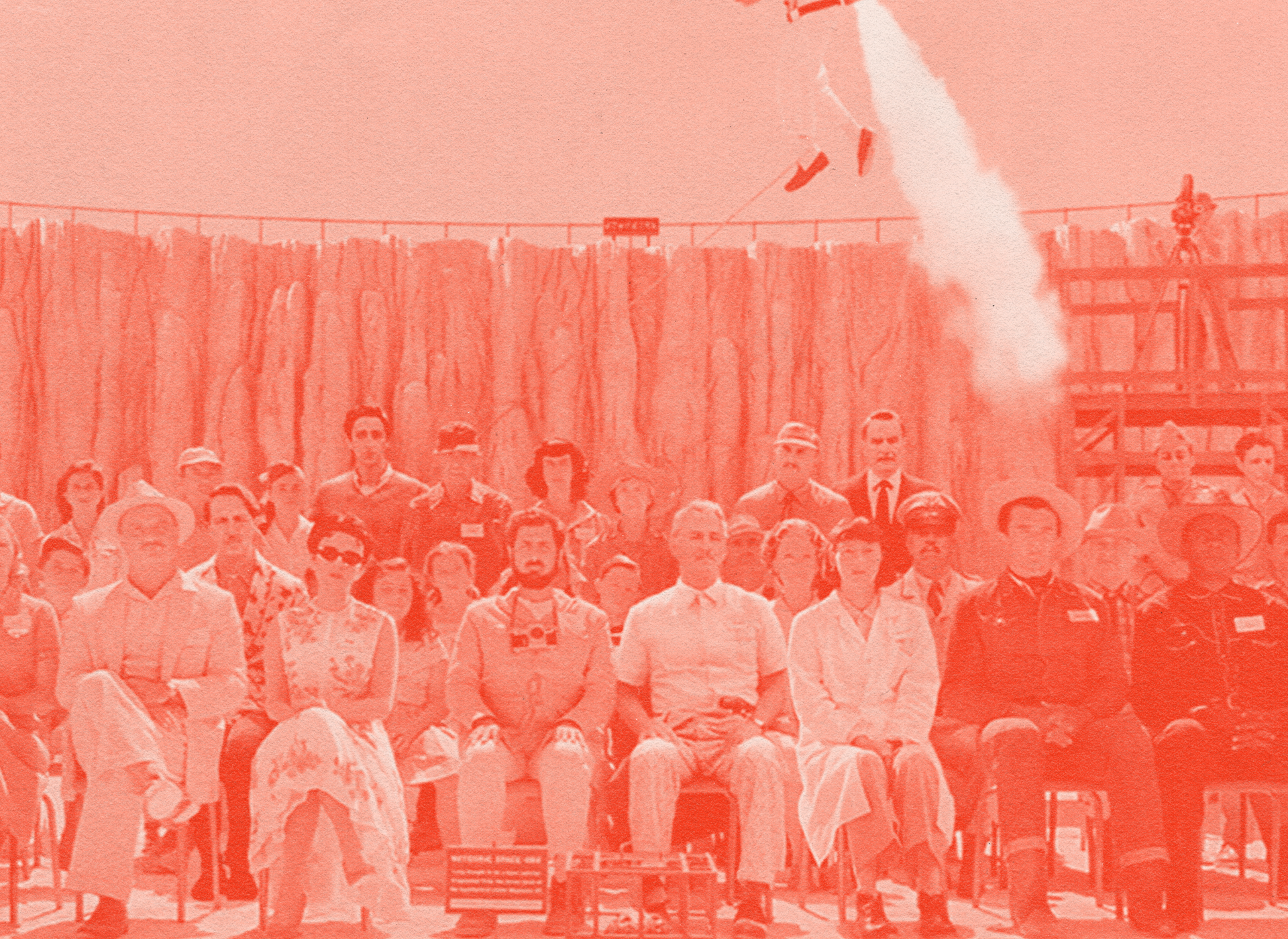

Those critics who didn’t immediately dismiss Asteroid City for its twee approach when it premiered at Cannes last May reached a consensus that the 50s-set film about the attendees of an astronomy convention for scientifically precocious youth who must deal with the fallout from extraterrestrial contact was a “profound meditation on grief.” Even though Anderson is one of our most consistent and prolific filmmakers, his advocates have a tendency to engage in apologetics. Such may explain why so many legacy publications have praised the film with that same buzzy phrase, creating a unified front against its detractors. Accidentally Wes Anderson has certainly not helped the director’s reputation as a legitimate artist, turning him into a living Urban Outfitters display for a generation that doesn’t want to address its own spiritual bankruptcy amid its quest for experiences and self-care, a reason its members are so enamored with his style but have yet to produce an artist who comes close to his caliber.

Those who discuss Asteroid City using such terminology try so hard to develop a taxonomy for its thematic concerns that mirrors assessments of Anderson’s style because they want to sever any personal connection to the film. They’ve watched the new Wes Anderson. They’ve opined on it. They can’t wait to see Schwartzman and Bill Murray in the next one. It doesn’t have to mean anything to them if they can turn it into a meme.

The problem is that Anderson has always been a director who feels and remains blissfully unconcerned with whether or not said feelings are easily compartmentalized. It’s why he has never shied away from placing unlikable protagonists in aesthetically pleasing worlds and making them realize their humanity by acknowledging their inability to stop hurting themselves and others. It’s also why when Anderson gets too raw as he did with the ugly American brothers navel gazing their way through India in 2007’s masterful The Darjeeling Limited, he has to retreat into claymation, coy frame narration, and period setting to become palatable once again after audiences and critics go lukewarm

With Asteroid City, Anderson bridges his recent work’s endlessly clever tendencies with the noxious but potentially loveable lost souls that cemented his status as a filmmaker in the late 90s. Schwartzman undertakes his first leading role for Anderson since Darjeeling as Augie Steenbeck, a renowned war photographer who must figure out how to tell his three children that their mother has died while they are on a road trip to drop off his eldest, Woodrow (Jake Ryan), at the convention. In between phone calls with his gruff father-in-law (Tom Hanks at his late-career best) after their car breaks down, Augie represses his feelings while finding himself in the orbit of Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), a Hollywood megastar whose daughter, Dinah (Grace Edwards), is also being honored at the festivities. But when a group planetarium session leads to an alien encounter, the festival’s government liaison, General Gibson (Jeffrey Wright), orders a quarantine, trapping the attendees against their will for the foreseeable future.

Anderson talked at length about how COVID polices and set protocols affected the film’s development on his Cannes press junket. Yet, predictably, critical conversations surrounding the film have largely ignored its preoccupation with the psychological effects of authoritarian action on individual autonomy. The Junior Stargazers descending on Asteroid City in the days of the space race are the best and brightest the nation has to offer. Consequently, Anderson positions the event as a ruse for General Gibson and his bureaucrats to seize the intellectual property of the honorees in the interest of national security. Shunned by their peers back home, the teen geniuses succumb to flattery. As Dinah tells Woodrow, “Sometimes I think I’d feel more at home outside the Earth’s atmosphere.” Their lives of forced isolation shield them from the reality of their exploitation. Only when the true costs of government overreach set in during the arbitrary quarantine do they rebel in a montage of anarchic wonder absent from the director’s oeuvre since the end of Rushmore.

Though Asteroid City may well be the definitive pandemic film, Anderson is less interested in allegorizing the state of America through Cold War comparisons than probing what happens to people left alone with themselves and forced to contend with the breakdowns of the worlds in which they have self-isolated. The death of Augie’s wife leaves him distraught, but, as Anderson implies, it is only the latest trauma that has slowly turned him into a cypher with nothing to cling to but his lofty cultural status. His guilt stems less from concealing his wife’s death from his children than his inability to nurture a loving relationship with the woman he knew he could never let love him back. Though he begins the film as the only character unphased by the mushroom clouds erupting from the town’s adjacent nuclear testing facility, he ends his time in Asteroid City with the realization that he’s built a career documenting the world’s conflicts so he won’t have to deal with his own.

Such explains his unlikely connection with Midge, who is beholden to an adoring public that refuses to let her break away from her sexpot roles. Like Augie, she latches on to her status, lost in perfecting the parts she’s offered at the onset of her decline to mask what she sees as her failure to be a good mother–even if she is a loving one. She remains too guarded to be honest about her feelings and can only think to seduce Augie through a live rehearsal of a nude scene from her upcoming film, effortlessly slipping into yet another role. Anderson tellingly opts to handle the millisecond flash of nudity with Johansson’s head out of the frame, a move that calls attention to how Midge has been fractured by her willing commodification. That Anderson shoots most of these interactions through the windows of cabins that are seemingly inches apart should be rejoinder enough for those critics who deem his meticulous style insubstantial.

As the quarantine takes its toll, Anderson remains focused on what happens to self-perception in the face of something bigger than ourselves, a goal for which his trademark ensemble class is game. Steve Carell’s motel manager and Matt Dillon’s mechanic assert dominion over their fiefdoms while fending off Liev Schreiber and Hope Davis’s proto-helicopter parents as they all come to terms with their vicarious living. Maya Hawke’s novice school teacher, June, clings to her prepared lessons on this field trip gone awry while her students challenge the script and her authority. Tilda Swinton’s Dr. Hickenlooper trusts the science and the fruits of her government contract until she begins to realize what she thought was the life of the mind was just myopia useful to her benefactors. She laments this realization in the film’s best line: “I never had children, but sometimes I wonder if I wish I should have.” Like Woodrow, Dinah, and their celebrity parents, her aspirations have insulated her from her humanity to the point that she can no longer discern her identity.

Borrowing the frame narrative that has become a hallmark of his work since 2014’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson constructs the film as a recreation of the type of documentary special on American theater productions that graced screens during the first Golden Age of Television. In what at first appears to be an attempt at ironic critical distance, Bryan Cranston narrates the production of Asteroid City, the latest play by Conrad Earp (Edward Norton), the fictitious renowned and rugged playwright of the West who resembles Ernest Hemingway as much as his two namesakes. Schwartzman, Johansson, and the rest of the cast seep into these various frames, sometimes their Asteroid City characters, sometimes actors left the fate of the ebbing and flowing careers attending method acting workshops and immersing themselves in their own romantic dramas.

In what may be the riskiest moment in any Anderson film, his actors playing actors stare into the camera and chant, “You can’t wake up if you don’t go to sleep.” By this point, the film has stripped them all of their affectations. It’s shown its nod to the 50s is less a yearning for the past than an admonition. Like Augie and Midge, we’ve come through our quarantine haze, realizing our profound sense of loss. Our embrace of nostalgia is an evasion of both our true selves and our fears that our lives and our country were never what we’ve made them out to be. But the mantra that ends Anderson’s film is not a call to action. It’s a consolation that the way we were is nothing to be embarrassed about. It’s what got us to this point. And now we can realize that we never really saved Latin if we’re willing to.

Asteroid City is now playing in theaters and available for premium digital rental.