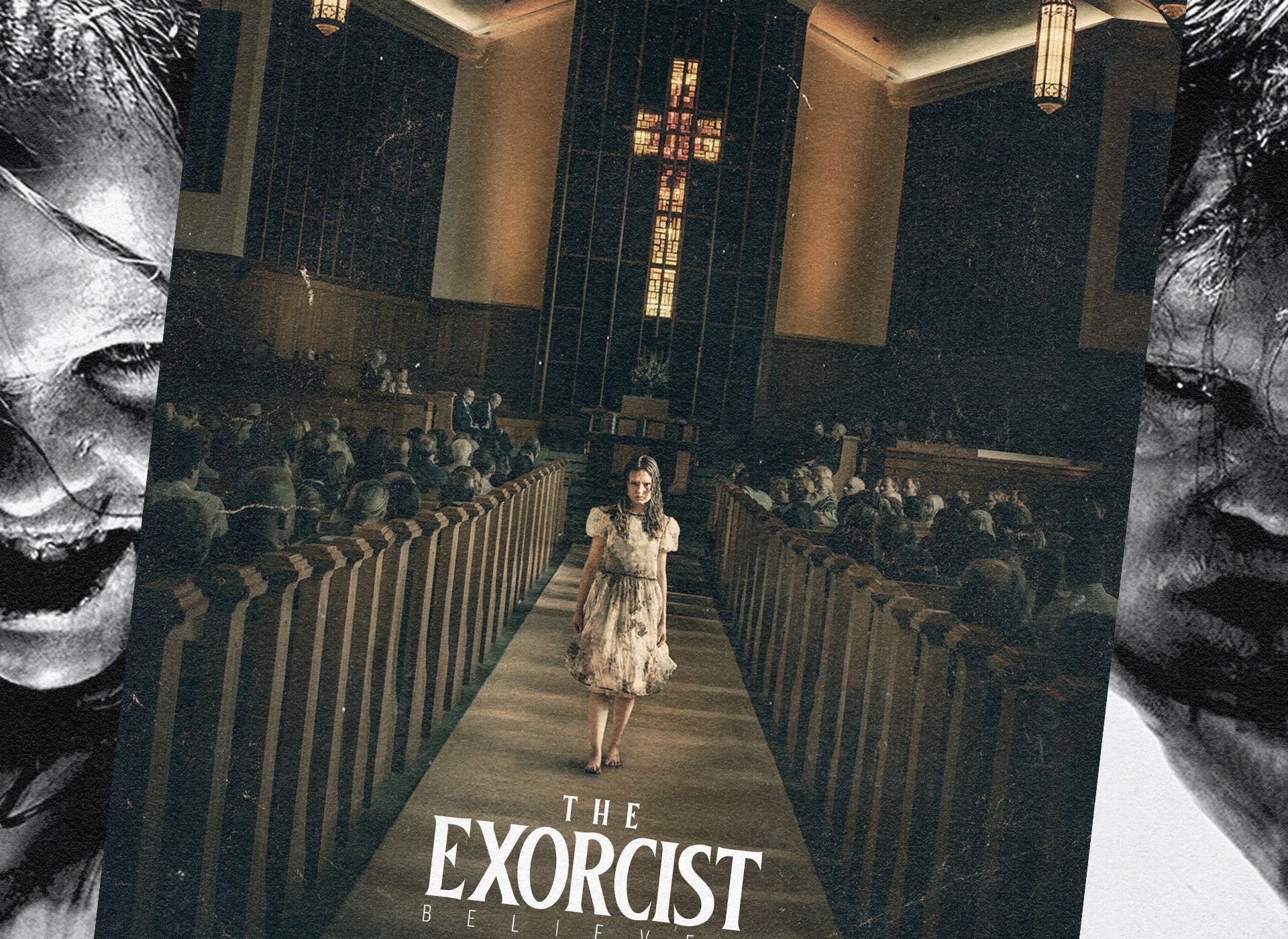

Local Color and 'The Exorcist: Believer'

David Gordon Green’s reimagining of the horror classic is the definitive portrait of the American South.

In his 2020 book, The South Never Plays Itself, self-exiled native son Ben Beard attempts to reconcile the region he calls home with its Hollywood representations. “The South is both a region and a thought experiment, real and fiction at the same time. The South is a place and an idea, but whose idea?”

Beard largely directs his interrogation of the South’s cinematic depictions at the Hollywood dream factory. However, the critical class bears as much responsibility in cultivating the stereotypes that have come to define the region. Entrenched in urban and (largely coastal) milieus, such critics long for cosmopolitan cachet, especially those that have left the areas of the country that pop culture deems unrefined. That’s the only explanation I can muster for the animosity that has met director David Gordon Green’s new chapter in The Exorcist series.

From a cursory glance, it appears that The Exorcist: Believer was marked from the start. Hollywood balked at the $400 million Universal Studios paid for the rights to a 50-year-old horror franchise that, despite four previous sequels and numerous imitators, has never come close to William Friedkin’s original. Its buzz further deteriorated when the studio announced Green was helming a new trilogy fresh from his controversial yet wildly brilliant take on Halloween.

One would expect that, upon its release, the film would take heat for being a derivative cash grab that attempts a soft reboot of the series by bringing back Ellen Burstyn’s Chris MacNeil and extending the universe to a new set of characters. Yet, the critical ire instead coalesced around the film's alleged lack of depth, a take best typified by D.C.-based Dead Central writer Mary Beth McAndrews’s contention that Green’s film “fundamentally misunderstands its source material and has nothing of any real substance to say.

The greatest strength of Green’s Halloween trilogy is its intimate understanding of small-town dynamics. Since beginning his career with indies George Washington (2000) and All the Real Girls (2003), Green has nurtured a talent for examining the South that substitutes a keen ambivalence for the tourist’s gaze approach Hollywood has turned on the region since the advent of the movies. While The Exorcist: Believer expertly employs the horror genre’s tropes, it is fundamentally a movie about place–namely the suburban Georgia town where single father Victor Fielding (Leslie Odom Jr.) must contend with the demon that has possessed his daughter (Lidya Jewitt) and her friend (Olivia O’Neill) after a preteen dalliance with the occult in the woods. Green not only relishes in but respects this semi-rural setting, presenting the half-bustling downtown where Victor owns a portrait studio and the renovated historical homes as only someone who has an intimate familiarity with Southern life and its often obviously overlooked class divides could.

Though pea-soup vomit and creative use of a crucifix have defined The Exorcist's legacy, Friendkin’s original is less a conventional horror movie than a study of secular upper-crust life in Washington, D.C., in which a force the city’s institutions have long thought they were above returns with a vengeance. In his new iteration, Green displays an immense understanding of the source material, but never shies away from how audiences outside America’s cultural hubs internalize a film so ubiquitous in popular culture.

Like Burstyn's MacNeil, Victor prides himself on his objectivity, an anomaly in the town to which he has fled after his wife died in Haiti during 2010’s earthquake, a tragedy that forced him to choose between her life and that of his unborn daughter. He begins the film hiding behind his camera’s lens on assignment in Port-au-Prince, presenting his version of reality until the real world intrudes on his insularity. From its first frames, Believer is a film about the pitfalls of representation and the frailty of those who think they have it all figured out.

Many of the thinkpieces about Green’s film have revolved around two dissonant poles: its alleged abandonment of Catholicism and its cultural appropriation. Such is the result of the movie’s choice to focus on a loose alliance of the town’s characters, including a Catholic priest (E.J. Bonilla), a failed novitiate turned nurse (Ann Dowd), a Baptist pastor (Raphael Sbarge) and a holistic practitioner (Okwui Okpokwasili) with ties to a confluence of Kongo and Christian spiritualities.

Yet, in this unholy amalgamation of the woke and regressive, Green has presented the most accurate and nuanced depiction of Southern Christianity ever put to film, a facet of his thematic concerns those with little knowledge of the region wouldn’t bother extending their frames of reference to understand.

Of course, Believer was never going to rival the cultural clout of The Exorcist. Such was never Green’s intent. Instead, the director has refracted an essential pop culture text through a Southern perspective, extending its resonance through regional sensibilities. The South has, indeed, finally played itself, and the reception is about what its natives would have expected.

The Exorcist: Believer is now playing in theaters.