Review: Oppenheimer

Christopher Nolan’s latest reminds us of the power of craft and the petty cultural criticism that preys upon movies of grand ambition.

One of the pandemic’s admittedly few pleasures was a years-long reprieve from pseudo-academic clickbait meant to drive a wedge between audiences. This journalism subgenre brought us profound insights on Bryce Dallas Howard’s stilettos in Jurassic World and Tarantino's take down from Time that exposed how often his films let women talk.

For a while, it seemed that Tumblr feminists had finally abandoned treating a one-off joke about women conversing on screen from a graphic novel as a pillar of critical theory. But then Barbienheimer announced that the movies were back, and a slew of hacks and desperate anons put away their vaxx pleas and odes to White Fragility for a shot at the next big thing.

The Right’s more unscrupulous personalities did nothing but self-harm with their Barbie vitriol, but at least they had something new to say. For those on the Left, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer was a moral affront: a movie about a great white man who did great white things in the directorial hands of a great white man. Before it even opened to the general public, the flurry of takedowns commenced.

Nolan’s film erased the Latin and Native Americas displaced when the government built its Los Alamos site (a hot take so steaming, its writer couldn't even be bothered to see the movie first). Not to be outdone, mid-level academic Tanya Roth spent the first half hour of a movie called Oppenheimer looking at her phone’s stopwatch in a sold-out theater before announcing that it took a woman 20 minutes to talk (and right before a sex scene, no less!). The response to Barbie retains an air of mean girl spite and budding incel fury.

But Oppenheimer’s reception is different. It’s a film about a once-in-lifetime talent nearly toppled by the has-beens and hangers-on of the bureaucratic class who bear more than a fleeting resemblance to its most vocal critics.

Nolan has earned a reputation for twisty narratives and camera trickery. However, his films have also long explored extraordinary individuals navigating professional jealousies and corrupt social systems that threaten justice and personal autonomy. It’s a throughline as apparent on the streets of Gotham and in the futuristic world of Tenet as for The Prestige’s magicians, the soldiers of Dunkirk, and Matthew McConaughey’s cornfed cosmonaut from Interstellar. In making his first foray into the biopic, Nolan frees himself from allegorical fantasy to directly engage with the thorny ethical questions that have shaped the contemporary world.

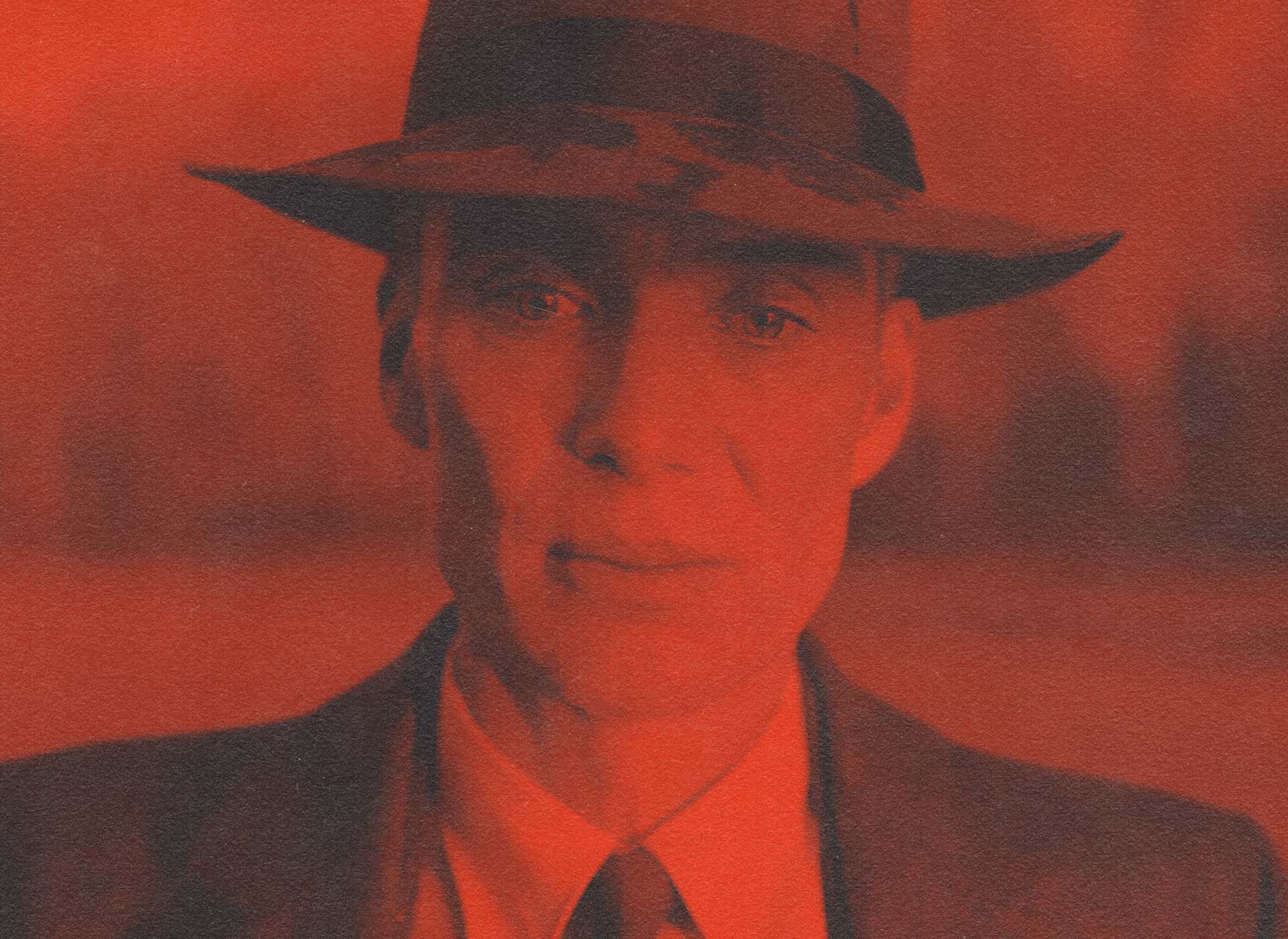

Fundamentally opposed to working with linear narratives, he divides the action among three pivotal moments in the theoretical physicist's life: Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) establishing the academic program that would lead directly to the Trinity project, enduring a Red Scare witch hunt to revoke his security clearance under the direction of U.S. Attorney Roger Robbe (Jason Clarke), and sitting on the sidelines as his former boss, Atomic Energy Council chair Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey, Jr.), undergoes a gutting confirmation hearing to become Eisenhower’s Secretary of Commerce.

Until Oppenheimer, David Fincher’s The Social Network was the gold standard of the “men in the room” biopic, a film still near unanimously considered the best of the 2010s. Like Fincher, Nolan knows how to shoot jargony legal hearings that are as compelling as action sequences. Yet, what has long justified Nolan’s reputation as a pantheon filmmaker is his ability to make such scenes purely cinematic. He’s the only working director who could take what should be the stuff of prestige cable, put it on a 70mm IMAX screen for three hours, and obliterate the memory of every summer blockbuster since Mad Max: Fury Road.

Oppenheimer is not a “Great Man” movie. It’s a story of how uncompromising vision clashes with duty. It doesn’t contain a midway stop moment in which Matt Damon delivers a land acknowledgment, but anyone seeing the film without a self-serving angle would know it’s both aware of such questions and explores why they were afterthoughts in the time period it so painstakingly recreates.

Florence Pugh’s Jean Tatlock may be the film’s first female to utter a line before doffing her clothes for most of her screen time. But she does so in a scene that reveals her ability to ideologically challenge Oppenheimer, all the while unafraid to embody what an alluring woman would actually look like in the 1940s. Not to mention, in a film of towering performances from Murphy, Downey, Damon, Pugh, and Josh Hartnett, it’s Emily Blunt as Oppenheimer’s put-upon wife who gets the movie’s best scene as she humiliates Robb during the kangaroo court of a hearing. Oppenheimer depicts its subject as an immutable yet flawed genius who earns the ire of his inferiors because he refuses to conform to a monolithic way of thinking. After this latest triumph, we should be saying the same about Nolan.