Dr. Ming Wang’s Persistence of Vision

The world-famous Nashville eye surgeon survived China’s Cultural Revolution. Now, he’s entering the world of the multiplex with a new movie about his life.

For Nashville natives, Dr. Ming Wang didn’t really need a biopic. He was already famous from the deluge of billboards and daytime TV commercials for the Wang Vision Institute that dominated local media throughout the early 2000s. A pioneer of both bladeless Lasik surgery and a patented contact lens made from placenta that can restore vision and correct eye scarring, Wang seems like the kind of doctor who would be tucked away in a third-floor suite at Vanderbilt Medical Center—respected by his peers and otherwise known only to those who suffer from the afflictions he can cure.

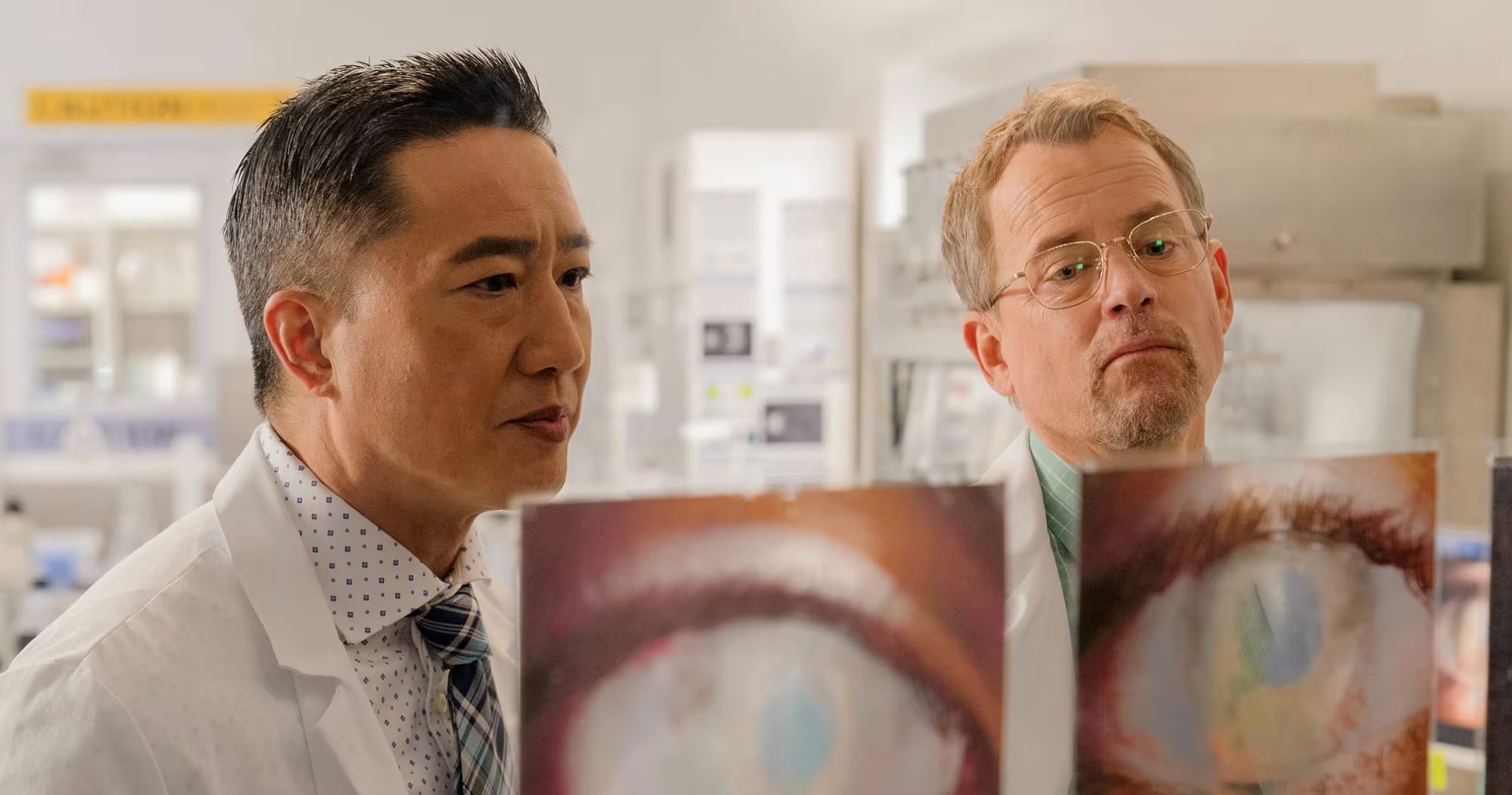

But his medical contemporaries aren’t well known for their flair on the ballroom dance floor or musical collaborations with Dolly Parton. They also didn’t have an $8.5 million film about their lives starring Terry Chen and Greg Kinnear that Sound of Freedom’s Angel Studios opened in 2,000 theaters nationwide during Memorial Day weekend.

Over the last two decades, Wang’s outsized persona and self-promotion have run afoul of Music City’s usual suspects. The Scene pushed back against his advertising claims in 2003 while the Tennessean has covered Wang’s film, Sight, skeptically—overly focused on its budget and making sure to Monday Morning quarterback its weekend box-office when it didn’t meet the expectations that producer David Fischer shared with the publication last week.

But Wang is a firm believer in the American Dream. He’s especially attuned to that oft-elided part about the nation’s obsession with eventually toppling its own idols because he witnessed firsthand the same tendencies that eventually devolved into the Cultural Revolution when he was a teenager growing up in China. “Sight is essentially a story of someone who used to not have freedom coming to America,” Wang said. “We're so blessed to live in a country with freedom. We need to appreciate it.”

Told largely via flashbacks, Sight crosscuts between 2007 when the Wang Vision Institute had become a fixture of Nashville and catapulted its founder into the American upper class and the doctor’s childhood in the early days of the Cultural Revolution. Wang is a brilliant surgeon who begins the film restoring the vision of a patient in front of an adoring press. But when a Catholic nun brings an Indian orphan to his clinic who was blinded by her stepmother to increase her value as a child beggar, Wang’s trauma from the past threatens to undo all of his achievements.

Given Wang’s involvement in financing and publicizing Sight, the film could have descended into self-aggrandizement. However, Wang is a figure that, despite his penchant for personal branding, is willing to grapple with his failures on the big screen. His greatest adversary in Sight is believing his rags-to-riches story a little too much. The film’s Wang is a pre-armor Tony Stark who refuses to address the traumas of his childhood–most clearly conveyed by the spectre of his first love with whom he lost contact after revolutionaries took her from her family.

Wang didn’t have to assign himself such a character arc, but it’s what elevates Sight above most other faith-based films. It’s not a movie that overtly focuses on Wang’s conversion, but one that shows the changes through his actions as he comes to terms with his limitations and his role in a bigger picture, a different type of subservience than what he was forced into during his childhood. “I'm a Christian,” Wang said. “My favorite testimony talk for Sunday services at churches is about how I believe God wants science and faith to work together. That's the essence of the film Sight. It’s about seeing beyond and fighting for rights.”

While Wang’s life story is a sterling example of American opportunity, it also counteracts the popular narratives that have remained woefully uninterrogated by cultural elites since the time he arrived in the country. When he was one of three students from his college invited to pursue higher education in the states, the greatest prejudices Wang encountered were not from rural white racists, but the Ivy League academic establishment that discouraged him from applying to medical school because he was Asian.

Likewise, despite Tennessee’s status du jour as a threat to democracy, Wang decided to develop his practice in Nashville because of its diversity. However, for Wang, that loaded term has a much different definition than the one espoused by the now-disgraced presidents and faculty of the schools that fought to keep him out.

Wang is much more interested in diversity’s unifying potential, one of the reasons he founded the nonprofit Tennessee Immigrant and Minority Business Group. “I think, as an immigrant, I have the duty and responsibility to pay back the freedom that I've come to enjoy and treasure, and to help build up America again,” Wang said.

Sight is at its most powerful during its numerous scenes of revolutionaries assaulting dissidents and forcing students to burn books—acts that Wang’s father describes to his young son as the behavior of people who do not understand honor and sacrifice. Though the film was long finished before this spring, one cannot help but make parallels between the destruction of books and buildings during the spate of anti-Israel student protests orchestrated across the nation.

It’s a trend that disturbs the real-life Wang, but that he also understands. “It’s attractive–some of those ideas from the Cultural Revolution because government gives you things,” Wang said. “Some young people have no clue. They never lived in a country without freedom.”

At the center of both Wang’s life philosophy and the film is a phrase Sight returns to time and again: “The present is made possible by the past.” It’s a mantra that’s woefully neglected in a society obsessed with either erasing or overcoming the more unseemly aspects of its history. But it’s also what has allowed Wang’s life in America to thrive.

Wang may have failed to protect his childhood sweetheart, but that has motivated him to perform 55,000 surgeries and found a nonprofit to restore vision to children from around the world. He may have made a movie that deserves a bigger audience, but there’s still plenty of time for Sight to find one.

He may have learned the erhu fiddle to evade the labor camps and join China’s traveling arts troupes, but it’s become the symbol of Wang’s life work. “The instrument I learned during the Cultural Revolution to survive in China now is a nice, beautiful instrument to bring East and West together,” Wang said. “I have a chance to express my appreciation to America while also sharing some of the best that Asian culture has to offer.”

Sight is now playing in theaters.