Halloween Ends and Our Postcultural American Moment

The alleged final chapter of the legendary slasher franchise takes aim at insularity and blind allegiance. That’s why it’s divided critics and fans.

Le Monde film critic and Cinémathèque française programmer Jean-François Rauger knew Eli Roth’s Hostel was the best American movie of 2006. Better than Martin Scorsese’s Best Picture winner The Departed or Paul Greengrass’s 9/11 docudrama United 93. Better than Clint Eastwood’s WWII double feature Flags of our Fathers and Letters to Iwo Jima. Better even than Borat or Babel. But Rauger was in the minority.

For most critics, Roth’s graphic horror opus about a Slovakian corporation that offers the option to slaughter vacationing millennial tourists to the global elite at premium prices was a violation of good taste with its blowtorches to the eyeball and postmodern fantasia of historical torture devices. For New York magazine’s David Edelstein, it was the quintessential example of “torture porn,” a term he coined in a positive yet tepid assessment of the movie that also applied to films as diverse as Rob Zombie’s The Devil’s Rejects and Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ.

As Edelstein wrote: “But torture movies cut deeper than mere gory spectacle. Unlike the old seventies and eighties hack-’em-ups (or their jokey remakes, like Scream), in which masked maniacs punished nubile teens for promiscuity (the spurt of blood was equivalent to the money shot in porn), the victims here are neither interchangeable nor expendable. They range from decent people with recognizable human emotions to, well, Jesus.”

This Halloween season, I’ve thought a lot about how Edelstein’s torture porn fracas unwittingly unleashed a critical bloodbath that hampered Roth’s career for nearly a decade. Not because Roth tacitly revisited the controversy during his stint on Quentin Tarantino and Roger Avary’s Video Archives podcast on its two-part “American Giallo” special this month or because it was the subject of my first published essay. Hostel is on my mind because, despite a bevy of polemic Iraq war films from those pre-Obama early aught years now relegated to freebie streaming channels (Stop-Loss? In the Valley of Elah?), it captured the cultural shift America would undergo in that Bush II midterm year, exposing the brute force and corporate collusion that governed American politics in the shadow of a downhome Bible-toter of a president while directly implicating its audience for consuming images of violence as entertainment. Critics and audiences just weren’t ready for Roth’s visceral indictment of an America whose horror would no longer remain repressed during the Great Recession two years later. Now, they’re not ready for Halloween Ends.

In her 2016 essay for The Nation, “What Art Under Trump,” novelist Margaret Atwood speculates on the shape of culture under the “fascist-in-chief” days after his election. While refusing to take a firm stance, Atwood cautioned the community for which she had so long served as a vanguard (and that would eventually try to cancel her): “…it’s tricky telling creative people what to create or demanding that their art serve a high-minded agenda crafted by others. Those among them who follow such hortatory instructions are likely to produce mere propaganda or two-dimensional allegory—tedious sermonizing either way. The art galleries of the mediocre are wallpapered with good intentions.”

Ever the prophet (and, not in that basic “The Handmaid’s Tale is like real life, guys” sort of way), Atwood pegged the artistic output of the past half-decade. Art adopted the guise of propaganda before not even bothering to obscure its intent anymore with the rise of COVID. Judas and the Black Messiah and The Woman King rewrote history as industry kingmakers snarled about alternative facts while showing the best they could do was dust off Borat or shake their heads in solidarity as Frances McDormand brought the plight of the working poor to life in Nomadland by shitting in a bucket. Those unwilling to take such nakedly political risks hid behind nostalgia, bridging legacy franchises with Trump Era twists that reached their nadir when an oligarch spouted the line, “You’re a nasty woman” to a girlboss paleontologist in 2018’s Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom.

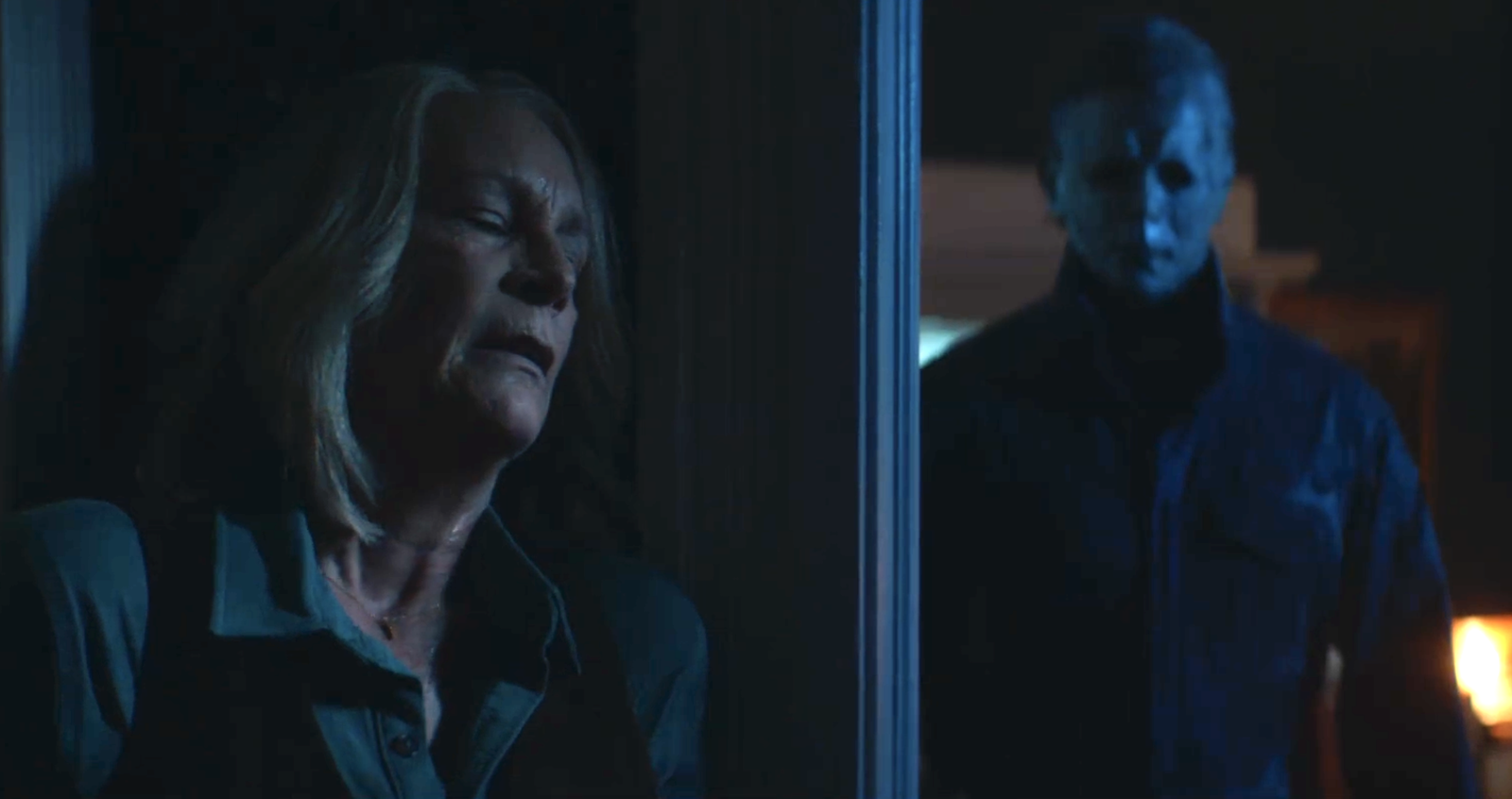

The reboot of Halloween that same year should have been more of the same as it earned $250 million dollars during its international theatrical run. Its marketing centered on the reunion between Jamie Lee Curtis’s Laurie Strode and masked killer Michael Myers forty years after the original film ushered in the slasher subgenre. Yet, while the movie did feature Strode as a trauma survivor taking back her power on its way to becoming, as Curtis tweeted, the biggest horror movie opening with a female protagonist AND a female protagonist over 55, it also served as an examination of the individual's responsibility to directly challenge unrepentant evil, a theme out of fashion in a culture that fuels itself on victimization and Manichean oppositions. Tellingly, Myers’s release after four decades stems from a government psychiatrist (Haluk Bilginer)’s curiosity about the ramifications of reintroducing him into polite society amid numerous scenes of the good doctor referring to the serial killer as property of the state.

In taking the reigns of the Halloween universe, director David Gordon Green along with his co-writer Danny McBride (the redneck jester best known as Kenny Powers from Eastbound & Down) managed to merge feminist overtures with conservative subtext while providing fanservice that more than sated a notoriously nitpicky subculture. However, unlike most of his studio counterparts, Green remained dedicated to subverting expectations as he signed on for the next two installments of his trilogy. Rather than cater to the legions of fan boys and girls or the whims of Film Twitter for Halloween Kills last year, Green kept Curtis confined to a hospital bed and away from Myers for most of the movie, much more concerned with how self-aggrandizement and myth converge in the formation of mob mentalities when a destructive force threatens a society. As my initial review of the sequel discusses, Green’s choice to reserve the most gruesome murder for the mob in a movie with ratcheted-up gore at the hands of Myers, shows an ambitious use of intellectual property all too rare in our perpetually rebooted culture.

While Kills proved less popular with critics and audiences, Green willfully resisted all semblance of Rise of Skywalker like atonement in his finale, likely the reason why Halloween Ends has the rare distinction of earning resoundingly low scores from critics and audiences alike on Rotten Tomatoes. Much of the fury stems from the film’s radical choice to push both Strode and Myers to the sidelines in what should have been a battle royale between two horror legends. Ever the contrarian, Green focuses on the relationship between Laurie’s granddaughter, Allysun, (Andi Matichak) and Corey Cunningham (Rohan Campbell), a once-promising townie who became Haddonfield’s pariah when he accidentally killed a young boy playing a prank on him during a babysitting gig. In the wake of Myers’s four-year absence, Corey has become the new boogeyman, a status that pushes him to assume a role as Michael’s protege and eventual successor.

Except it’s not as simple as all that. Green’s refrain throughout his Halloween trilogy has remained that evil never dies, it lingers whether in the folly of those who think they can control it or the PTSD of those like Laurie Strode. But in this final chapter, the director bridges two interpretations of Myers’ iconography: John Carpenter’s nihilistic view from the original movie that evil merely exists and Rob Zombie’s oft-maligned take in his 2007 and 2009 Halloween remakes that evil is a product of one’s environment.

Green’s strength as a filmmaker has always been his dedication to dissolving the surface of things whether in his stoner comedies like Pineapple Express (2008) and Your Highness (2011) or his Southern indie dramas like Joe (2014), All the Real Girls (2003), and his debut, George Washington (2000). Consequently, he refuses to mythologize an unrepentant evil or psychoanalyze a presence like Myers into the upper echelons of pop culture ala Jeffrey Dahmer. Instead, he opts to make a movie about how the people who thought it was a good idea to dress as Dahmer after binging that new show on Netflix contribute to the pervasiveness of evil that leads to cultural rot.

Given that Green established his style crafting stories set in Flyover Country, the most expected—and welcome— element of Halloween Ends is the film’s deft scenes of smalltown life (Curtis shopping in a disheveled IGA, the town doctor showing off his gauche pad to impress a nurse he would have kept #MeTooing had Corey and Michael not enacted their own bloody display of callout culture). For Green, no one gets off easy and every decision is a sacrifice. Laurie Strode remains the film’s final girl, but the movie makes clear her focus on self-preservation permitted much of Myers’s mayhem to occur unchecked. She didn’t push back on authorities and their platitudes as she prepped herself for her battle these past 44 years. She never asked the questions or confronted the mob’s perception of her before their ire turned to Myers and, eventually, Corey.

In the end, Laurie is not a messianic leader delivering her town from evil as much of a blast as her showdown with The Shape is in the film’s third act. She’s flawed and governed by her own fears. But, she realizes that feigning those fears are motivated by anything other than self interest or are in service to an imagined greater good fuel the mob mentality that is the movie’s true villain. She also realizes even though Halloween does, in fact, end, healing cannot begin without one final display of mob rule as the film concludes. She has come to terms with her sins and made dispatching Myers a public ritual. She’s admitted to her role in the trauma Myers (or his Rorschached real counterparts from COVID to the failed War on Terror) has inflicted for decades. Still, her fellow citizens aren’t quite ready to let go or acknowledge their own complicity. Clearly, the same is true for much of Green’s audience.

Halloween Ends is still in theaters and available to stream on Peacock.