Radical Objectivity

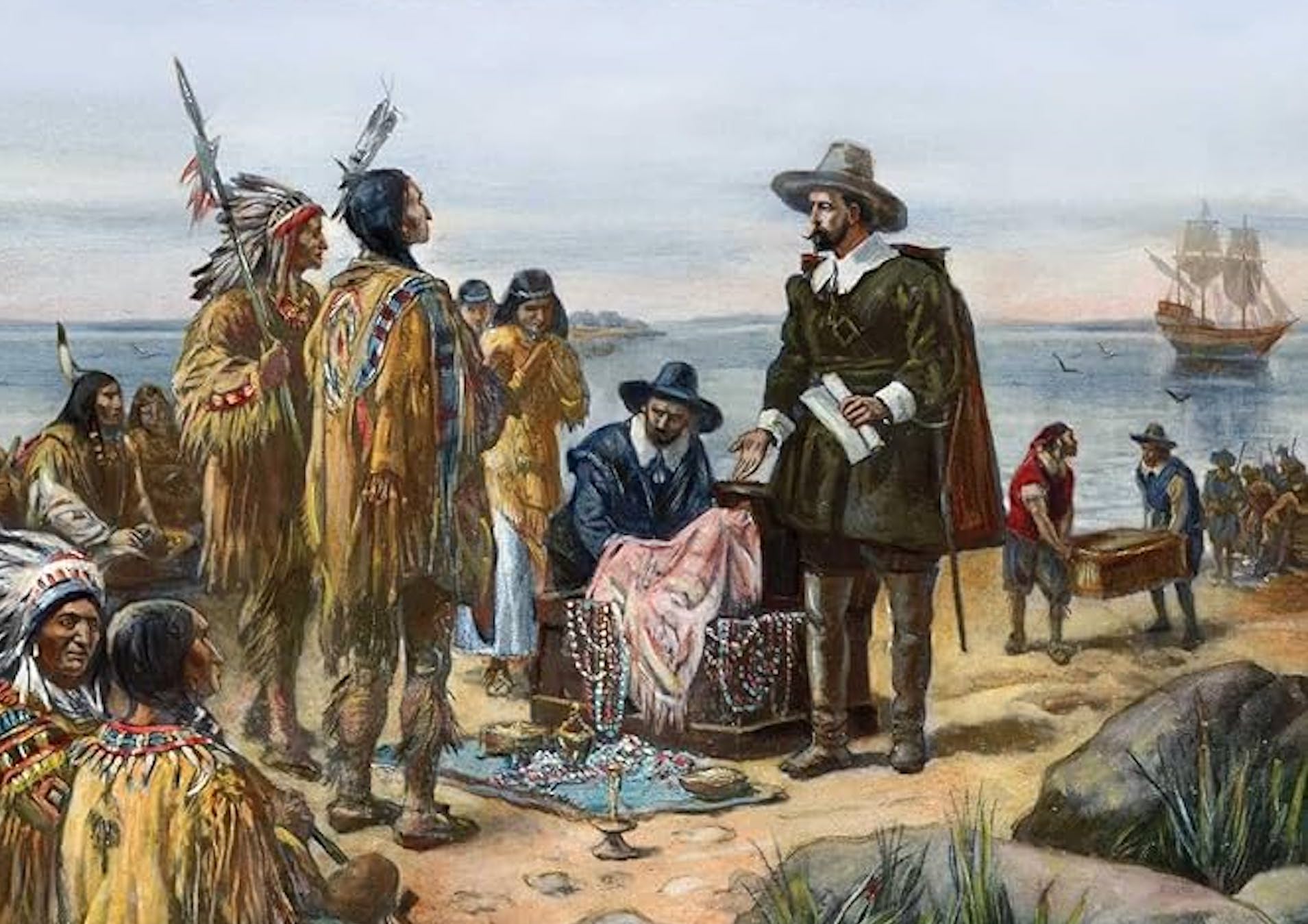

A review of Jeff Fynn-Paul’s 'Not Stolen: The Truth About European Colonialism in the New World'

The citizens of Toms River, New Jersey, were finishing their Halloween candy and scraping the pumpkin residue off their porches. But Shawn Michaels, a DJ for local adult contemporary WOBM, had more on his mind than the latest from Miley and Dua Lipa. “Now that Halloween is over next up is Turkey Day! So it's not surprising that the conversation involved getting ready for Thanksgiving. The question is ‘Are Pilgrims racist?’” the storied broadcaster wrote on the station’s website.

To his credit, Michaels managed to weigh the pros and cons. However, that such a controversy was the primary topic on the most benign radio station in suburban Jersey shows how all-encompassing viewing America through the lens of race has become. What was once the purview of fringe academic circles and professional activists has encroached into every facet of American life. If the historical record did indeed demonstrate evidence of such widespread blind hatred, America would be long due for a reckoning. But as Dr. Jeff Fynn-Paul discusses in his vital new book, Not Stolen, not only is this portrait of America inaccurate, but contemporary academics have retconned centuries of historical research to prop up this specious lens.

Fynn-Paul is an established academic who serves as a lecturer in the school of Social and Economic History at Universiteit Leiden in the Netherlands. His work on urban development in the late medieval and early modern period has resulted in a laundry list of peer-reviewed publications. With two books about Iberia on his CV, Fynn-Paul is uniquely positioned to write about the origins of the New World, familiar with the field’s body of research and the current trends shaping the discourse.

After seeing the discipline of history (and the academy itself) devolve into ideological claptrap, Fynn-Paul wrote the book as a corrective—a decision that could have irrevocable consequences for his career. Regardless, Not Stolen is unsparing in its contempt for activist scholars: “This ‘Indians’ are always good, Europeans are always evil’ habit has become so ingrained, that the result is a sort of reality creep, where the academy gradually loses touch with historical facts, as they subsist year-in and year-out on a diet of books that continually stretch the truth in a single direction,” he writes.

Consequently, Fynn-Paul employs his book to stage an intervention. His goal is not to offer up fresh groundbreaking research, but to restore the academic conversations that historians have engaged in for decades within one cohesive text. Not Stolen posits that our CRT-ified current moment stems from a handful of books written largely by academics with no historical training such as Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States (2014), David Stannard’s study of New World genocide American Holocaust (1992), and Bruce E. Johansen’s Forgotten Founders: How the American Indian Helped Shape Democracy (1982).

Though most trained scholars dismissed such research for lacking rigor upon its release, it has gained cultural cachet in recent years as writers like Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky, and Ibram X. Kendi have proven a boon for book publishers. The result is that academic consensus has dissolved since the advent of the Trump era, melding with popular sentiments that activists have exploited for professional and personal gain as they colonized stalwart institutions. Since most of these scholars unabashedly hold Marxist views, they operate under a revised theory with race standing in for naked class struggle as their ideology evolved after the Cold War. As a result, they willfully overlook how their arguments apply to Russian and Chinese contexts while they fuel anti-American sentiment, which could have damning real-world consequences in the realm of foreign policy.

Working within this context, Fynn-Paul course corrects the myths that have threatened to taint every aspect of American life as he culls together an impressive body of academic citations. Taking issue with the terms “genocide” and “massacre,” Fynn-Paul argues that the tales of blood-thirsty pioneers spoonfed to school children are embellishments of a few incidents that have left an outsized stain on the American experiment. The percentage of Native Americans in comparison to the general population has remained markedly consistent since 1810. Genocide was never an official policy of the U.S. government. Alleged massacres resulted in the deaths of less than 1% of the Indian population and numbers in the thousands, not millions–a record long obscured thanks to Stannard’s embellishment of native population estimates. Colonialism is not an outgrowth of capitalism because the church and nobility were fervently opposed to such economic systems. The “logic of tribal anarchy” meant no land was in possession of one tribe for more than a few generations and natives were invariably locked in intratribal disputes. No evidence exists that settlers engaged in biological warfare by giving natives smallpox-laced blankets. In fact, Thomas Jefferson established an immunization program for Indians, going so far as to task Lewis and Clark with disseminating the smallpox vaccine on their famed expedition.

Fynn-Paul is not an apologist for American atrocity; he is a realist dedicated to putting such blunders in their proper historical context. “Is it [the U.S.] any less ‘worthy’ than Russia, Iran, or China, which were built on the displacement and extermination of much larger minority groups–some of which is still ongoing today? Is it any less ‘legitimate’ or ‘worthy’ than an African country with a history of pre- and post-independence ethnic cleansing? What about Nigeria, whose slaving Empire of Benin enabled the transatlantic slave trade by selling captured African rivals to Europeans and Muslims alike?”

In a work of impressive scholarship, Fynn-Paul’s greatest strength is his ability to turn the post-structuralist theory of Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida that has given a second life to Marxist thought in on itself. Those who demonize America practice a faulty logic in which, “Settler colonialism is ‘Western exceptionalism’ because, even though it is rabidly anti-Western, it nonetheless assumes that Western civilization is exceptional.” Anti-capitalists who believe truth is relative commit the intellectual sin of not understanding that, according to their theoretical bent, “There is no such thing as capitalism per se-because there is no such thing as not capitalism either.”

As expected, Not Stolen has faced an avalanche of criticism, much of which is anonymous and the work of those who have not read it, including a semi-viral campus magazine post by an alleged student of Fynn-Paul’s entitled “What do you do when your professor writes a book justifying European colonialism and wants to talk about it?” Yet, in a climate marked by what Fynn-Paul calls “internet-driven presentism,” such passionate responses from critics who would never deign to entertain counterarguments are expected. Not Stolen may not mark a turning of the tide for the academy’s decline, but it’s a reminder that there are still pockets of resistance dedicated to the pursuit of truth.