There Is No Culture War

How a status-obsessed critical class and creators entrenched in their dogma poison fruitful discourse

The first person that esteemed social psychologist Dr. James Martin told about the time he almost committed suicide after a demon named Nefarious possessed him was Glenn Beck. For longtime fans of the Obama administration’s Public Enemy #1, such may seem like just another segment on Beck’s Blaze Media. But Dr. Martin isn’t real; he’s the main character in last April’s demonic possession movie Nefarious.

The film’s “R” rating and nods to Hannibal Lecterish banter between psychologist and evil entity possessing a convicted serial killer were tailor-made to reel in casual moviegoers. Those that didn’t know they were in the hands of Christian movie heavy hitters could only groan when they realized Nefarious’s plan: the demon was going to make the good doctor realize his liberal politics prevented him from seeing himself as a murderer, including of the unborn child his girlfriend was conveniently aborting at a Planned Parenthood this very moment in the plot…

When a bevy of conservative influencers flocked to the film’s premiere, no one seemed to care about its garish aesthetics or muddled thematics. Social media pages were awash with variations of the same rave: “This is how conservatives win the culture war.” No, Nefarious and films of its ilk are not how “we” win the culture war. There is no culture war. And unless conservatives stop using such manufactured conflicts to make up for their lack of critical engagement and neglect of artistry, any semblance of a unified American cultural fabric will remain the stuff of fantasy.

While the concept of the culture war has murky origins, it entered the pop culture lexicon when sociologist James Davison Hunter released his book Culture Wars: The Struggle To Control The Family, Art, Education, Law, And Politics In America as the 1992 election’s primary season was in its natal stages. Hunter argues that the popularity of Reagan’s Cold War policies paved the way for his easy election dominance in 1984. However, it also galvanized a progressive media and academic elite to push back from within the realms they still controlled. Such led to an uneasy alliance between evangelicals, Catholics, and Orthodox Jews in combating what they saw as an existential threat to American values.

Though compelling, Hunter’s assessment is far from comprehensive. The book skirts the role of liberal establishment figures like Joe Lieberman and Tipper Gore in targeting protected artistic speech to justify increased overreach of government bureaucracy. It also elides the rise of aligned nonprofits like the defunct Parents Music Resource Center responsible for the Parental Advisory stickers that continue to indiscriminately mar album art. Likewise, Hunter’s immersion within academia leads him to dilute the role indoctrination in higher education has played since the 60s counterculture, a blindspot on full display in a recent interview with Politico in which he states, “What used to be the province of intellectuals now became the province of anyone who had access to higher education, and higher education became one of the gates through which the move to middle class or upper middle class life was made.” That Americans seeking said upper-middle-class status through academic and creative class jobs must first prove their fealty to the party line doesn’t seem to register.

Such caveats aside, Hunter’s concept of the culture war became fodder for upstart conservatives like Pat Buchanan, who longed for a return to the Reagan dogfight and a shift away from Bush Sr.’s country club Republicanism. Though Buchanan failed in his primary challenge to Bush, his infamous “Culture War Speech” at the 1992 Republican National Convention took Hunter’s concepts beyond the realm of academia and into the mainstream. Haranguing the “Malcontents of Madison Square Garden,” Buchanan made a case for the Americans that assaults on tradition and the nuclear family would most affect: “They don’t read Adam Smith or Edmund Burke, but they come from the same schoolyards and the same playgrounds and towns as we come from. They share our beliefs and convictions, our hopes and our dreams. They are the conservatives of the heart.”

Although Buchanan’s speech unleashed the idea of a culture war into American politics at large, it had the unfortunate consequence of extending Hunter’s quite specific definition of the concept as a fight to preserve traditional values into an issues grab bag that claimed everything from Clinton’s draft dodging and support of the “homosexual rights movement” to school choice. What results is politics as a zero-sum game in which pro/con dichotomies quell political debate and contribute to irreparable differences.

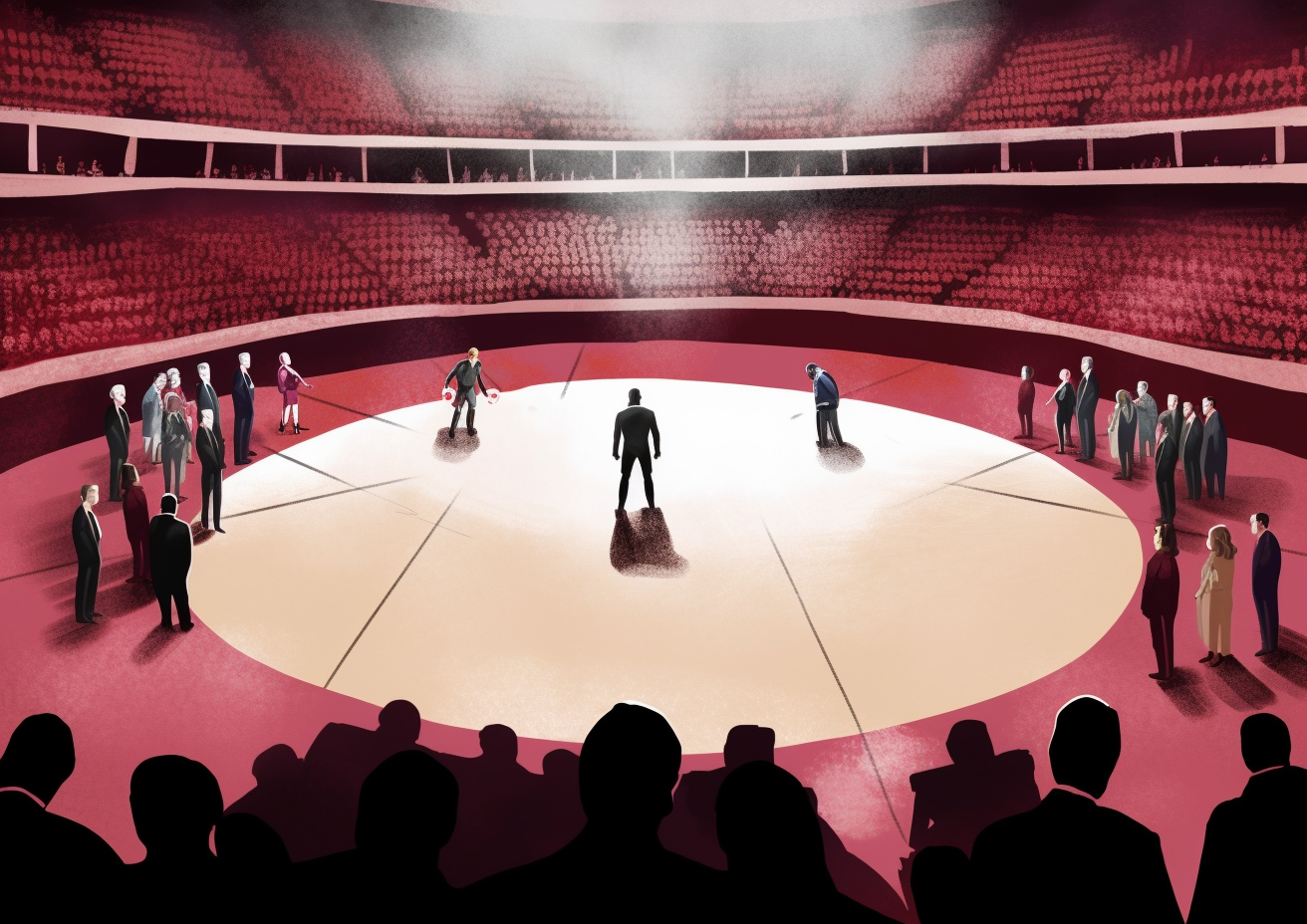

In both Hunter and Buchanan’s views, a culture war involves two politicized sides intent on annihilating each other’s worldviews. However, such a conflict hinges on a self-installed godhead in the form of an academic or political man of the people telling these conservatives and liberals of the heart what they should value and find vile while setting up a path to success for the budding grad student and online outrage monger alike who hope to follow in their footsteps.

Those with whom Hunter bandied about the faculty lounge were far more concerned with culling together disciples and carving out their own esoteric academic territory than instilling keen critical acumen in their charges. Those that Buchanan met on the campaign trail may well have read Smith and Burke; it just likely didn’t occur to him to ask before conscripting the poor rubes into yet another war that benefits the political class. Yet, both know deep down that a populace with a hunger to read The Wealth of Nations and Reflections on the Revolution in France would be too concerned with engaging culture to go to war over it. Such citizens don’t need a Buchanan or an e-girl quoting Ephesians while railing against Hollywood’s values under yet another picture of her posing in a crop top. They also have the discernment to know that Nefarious isn’t a good movie.

Conceptually, the culture war may exist, but the top-down declarations of Hunter and Buchanan betray that whatever conflicts such terms are supposed to encompass are anything but accurate. By definition, a war relies on combatants with rigorous training who are prepared to face the enemy with an array of strategies. Those conservatives who unwittingly find themselves on the front lines of today’s culture war have but few options.

They can blindly fuel the outrage machine by lashing out at media conglomerates. But such foaming at the mouth often backfires as was the case when Universal delayed the release of its satirical horror movie The Hunt in 2019 due to conservative anger over the concept of refined liberals picking off deplorables in The Most Dangerous Game fashion. If such pearl clutchers had bothered to see the movie (or even watch the trailer), they would have experienced a ruthless evisceration of the coastal elites that also took the time to develop dimensional working-class characters. But the backlash worked all too well. The movie was unceremoniously dropped into theaters the week before COVID and was quickly forgotten when it could have been a blockbuster that challenged audiences on all sides. Anyone still mad about the same-sex kiss in Lightyear would do well to remember this.

More effectively, those espousing traditional principles can vote with their wallet. Embodying the maxim of “Get woke, go broke” has become a reinvigorated pillar of conservative activism as Bud Lite and Target reel from their gender goblin missteps and the Right sets their sights on less egregious offenders like Chick-fil-A and Cracker Barrel, expanding their territory through forced atonement for DEI sins. Such strategies may cause temporary stock tumbles or mid-management shake-ups, but the results are purely cosmetic.

Those in charge will either continue to believe the latest progressive blather or wager that aligning their corporate ethos with it is better for their bottom line in a world where ESG investing exerts increasing pressure on publicly traded companies. More importantly, refusing to purchase a polyblend T-shirt made in China from one store in favor of the same product elsewhere amounts to little more than a lateral move in a global marketplace.

A certain stock of good solider can always go the route of Nefarious and the hundreds of Christian productions that preceded it. But that film’s misleading marketing divulges the increased inefficacy of such cultural production. The Jesus Revolution achieved notable success last spring as a movie about faith aiming for a big tent, indicating little mileage is left in merely preaching to the choir.

If we are indeed in a culture war, bad Christian melodrama and rah-rah patriot fables made on shoestring budgets to resist Hollywood while imitating its worst tendencies are the equivalent of fighting tanks with pebbles. Until the conservative kingmakers adopt a strategy of incubating contrarian talent akin to what Michael Anton deems “The Tom Wolfe Model” after the white-suit-clad gadfly of the New York chic, the art of the Right will remain akin to crayon sketches parents stick on the fridge because it’s their duty to be proud.

Indeed, the idea of a kinetic culture war is such a fiction that, as anyone who has recently ventured to the multiplex can attest, the entertainment industry has largely ceased to cater to broad demographics, content resting on the laurels of fanboy approval, film fest kudos, and critical accolades that elevate a film simply because its politics are in the right place. Nefarious shared its debut weekend with the eco-thriller How to Blow Up a Pipeline, an adaptation of Andreas Malm’s treatise that instructs readers in campaigns of industrial sabotage and terrorism to combat climate change.

The film continues to sit pretty at a 94% Rotten Tomatoes rating while earning cache for being a “persuasive prince of activist messaging” (Vanity Fair), exhibiting “palpable anger emanating from a betrayed generation” (Independent), and succeeding as “an incendiary political barnburner” (Detroit News). The weekend before saw the wide release of the Sundance-winning A Thousand and One, a tale of systemic inequality featuring a single mom who kidnaps her son from foster care after being released from prison and tries to survive on the streets of Guiliani’s New York. Despite its 96% fresh score, the film was out of theaters in less than two weeks and already seemingly forgotten. Even with endless coverage in the arts section of every major media outlet, the combined gross of both films was less than half of the 33% rotten Nefarious’ admittedly modest $5.1 million box-office take.

The dismal financial performance of both projects does not give license to conservative culture warriors to gush when a marginally successful movie of the Right outperforms a lefty indie. But it does reveal the disconnect between the measurable public interest in the issues of our time and the press coverage they receive. The commercial failure of last spring’s indie darlings exposes the brazen intellectual dishonesty of arts criticism. We are not soldiers in a culture war, but the inadvertent participants in a tastemaking regime for which we never prepared between our snarky tweets and jokes about how the Left can’t meme.

Some well-exposed handheld cinematography aside, How to Blow Up a Pipeline and A Thousand and One are as contrived and shallow as Nefarious, their characters existing solely to function as mouthpieces for the ideologies to which their filmmakers are in thrall. Pipeline’s rainbow coalition perfectly captures Taika Waitita’s off-the-cuff dismemberment of Hollywood’s diversity initiatives in which the indigenous director of Thor: Ragnarok and JoJo Rabbit remarked, “I never grew up with a group of friends where there was someone who represented every ethnic group in my group of friends. I don’t know who the hell grew up like that.”

Perhaps the film’s antiheroes didn’t grow up like that, but the moonbeam unity they generate from the common goal of destroying the titular pipeline in Texas could make for one banger of an 80s Coca-Cola commercial. There’s the redneck family man who lost his farm to the oil companies thanks to eminent domain; the North Dakota reservation teen who likes to sucker-punch itinerant frackers; the white college dropout who thinks recycling campaigns just aren’t enough; her biracial lesbian twentysomething bestie with terminal cancer caused by poisoned water near a refinery; and her black nurse girlfriend who embraces terrorism for love. What modicum of suspense the movie has is less the result of an unlikely team coming together to defy the odds ala Danny Ocean and his eleven or twelve, but, tellingly, whether or not these inept products of helicopter parents will accidentally blow themselves up in the process. Paranoid thrillers like The Parallax View and The China Syndrome would have ended on a note of futility, an introspective and self-critical meditation on their politics. But How to Blow Up A Pipeline winds up exactly how one would expect post-2020: triumphant Gen Zers whose arrests go viral, making the cause all about them.

Its impressive performance by Teyana Taylor aside, A Thousand and One never evolves beyond limp melodrama and CRT platitudes. As Inez, Taylor spends the film mad at the world, spouting lines like, “Nobody give a shit about black women except other black women.” Somehow, director A.V. Rockwell seems oblivious to how Inez’s pattern of abuse toward a host of black female friends and acquaintances that go out of their way to help her throughout the entirety of the movie’s interminable 117 minutes undercuts such profound statements.

But that doesn’t really matter because there are endless shots of the Times Square Old Navy and Chuck E. Cheese scored to sound bytes of Rudy Guiliani and Michael Bloomberg advocating broken window policing. Not to mention that moment when Inez’s son, Terry, gets a taste of the old stop and frisk in a scene as overwrought as any in an afterschool special. A filmmaker searching for truth instead of festival buzz would have harnessed a talent like Taylor to create a complex character portrait.

Instead, Rockwell sums it all up with, “Damaged people don’t know how to love each other, that’s all,” a throwaway line that accidentally captures America’s disturbing dearth of personal responsibility. Amid the film’s utterly unearned twist ending, Inez leaves us with a monologue about loving herself. She’s yet another victimized hero who could well be a character excised from How to Blow Up a Pipeline’s script in its early stages.

While such polarized issues movies are not a recent development, their all-too-predictable critical reception is. The American Film Renaissance of the 1970s arguably began when Pauline Kael released her 5000+-word defense of Bonnie & Clyde that rescued the now classic from B-movie oblivion and resurrected film as the dominant form of popular culture. Though the movies of the time belonged to what Robert Ray deems the Left and Right cycle that refracted the period’s political tumult, they held a broad appeal–more concerned with interpretation and conversation than proselytizing.

Dirty Harry is an antiauthoritarian fascist whose vigilante assassination of the Scorpio killer made the silent majority cheer as much as his mocking of the police sated the counterculture. The Graduate’s Ben and Elaine stick it to their parents’ California plasticity, but their uneasy gazes as they ride away from the church lead to the realization that they will one day become what they reject. The double bills of the era were in dialogue with each other, popular entertainment that only bettered the cultural milieu. Such days are long gone.

In Culture Making, theologian Andy Crouch cautions that, “The danger of reducing culture to worldview is that we miss the most distinctive thing about culture, which is that cultural goods have a life.” The most vocal proponents of the culture war claim to fight to preserve the American way. In reality, the conflict in which they so fervently believe is the true existential threat. The most ardent culture warriors aim to trap us in our worldview where their inferior products can claim a monopoly over the life of the mind. With the rare exception of an Armond White or Kyle Smith, the Right's view of cultural criticism amounts either to pointing out the woke moments in The Batman and The Little Mermaid or staying within the realm of the high arts that remain the purview of stalwart publications like The New Criterion—the urbanites behind enemy lines who do, in fact, read Adam Smith and Edmund Burke on a regular basis.

There is no culture war. But there will always be those who want to send us into battle anyway. And the only ones standing between tribalism and outrage profiteering are the critics willing to delve deeply into cultural experience to expose this conflict for what it truly is: nefarious.

- Nefarious is now playing in theaters and available for digital rental.

- The Hunt is now streaming on Peacock.

- How to Blow Up a Pipeline is now available for digital rental.

- A Thousand and One is now available for digital rental.